My Professor and My Brother-in-Law:

A Dual Eulogy and Appreciation.

Within the course of 24 hours recently, I learned of two significant deaths, each of which affected me greatly emotionally, but also left me with gratitude for their presence in my life. And they made me think about what unites people across seemingly large divides.

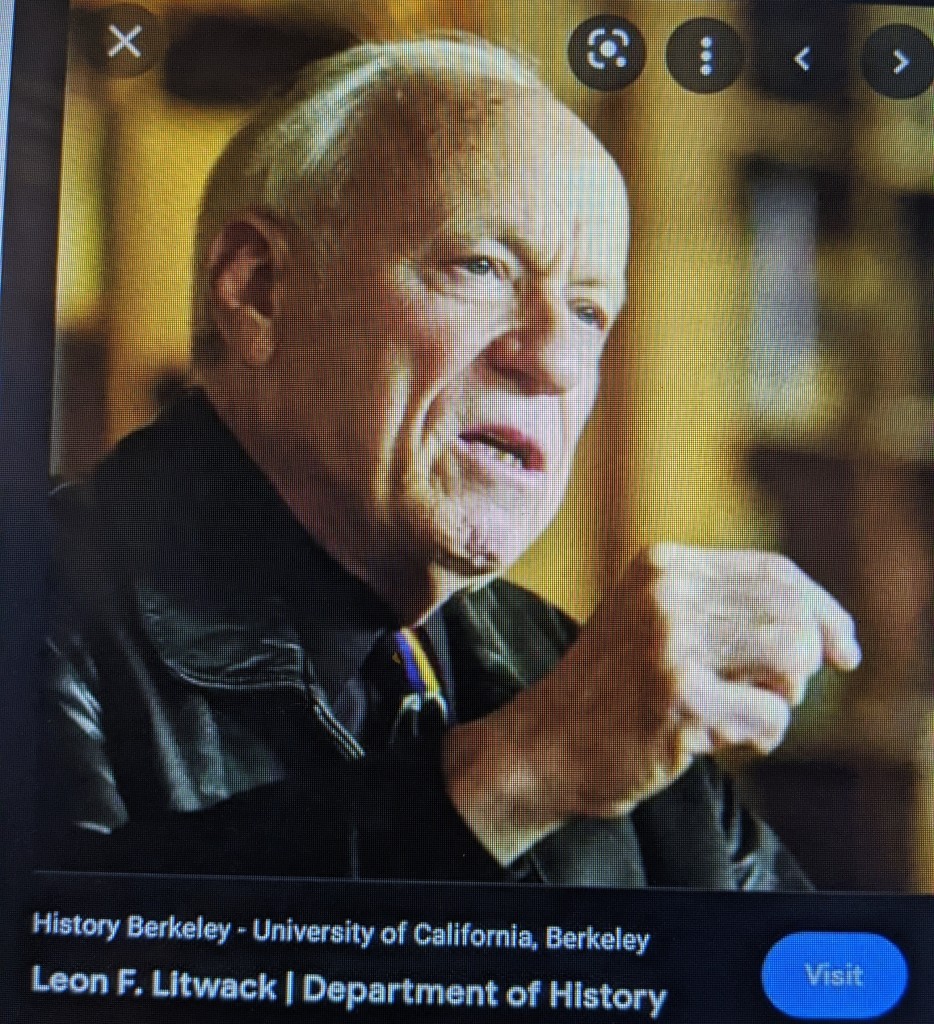

First, my graduate school mentor, Leon Litwack, passed away at the age of 91, at his home in Berkeley, California. He was surrounded by his beloved books, soon to be part of the storied Bancroft library at the University of California, Berkeley (he had said shortly before that he wished he could take them with him), and Rhoda, his wife since 1952. Leon taught history at UC Berkeley from 1964 to 2010, and changed the course of scholarship in American history through his teaching and publishing. The email informing a group of us of his passing mentioned that towards the end he no longer listened to music – a sure sign that he was ready to go. He loved to quote a line from Robert Palmer’s book Deep Blues: “How much history can be communicated by pressure on a guitar string?”; and once, driving me to some place in Berkeley in the mid-1980s, he told me and another person with us that day of his recently discovered love for country music, to go along with his equal passions for blues, rap, Beethoven, Mahler, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Creedence Clearwater Revival (whom he knew as young aspiring Bay Area rock musicians), and the early U2. For him, once there was no music, there was no life to be had.

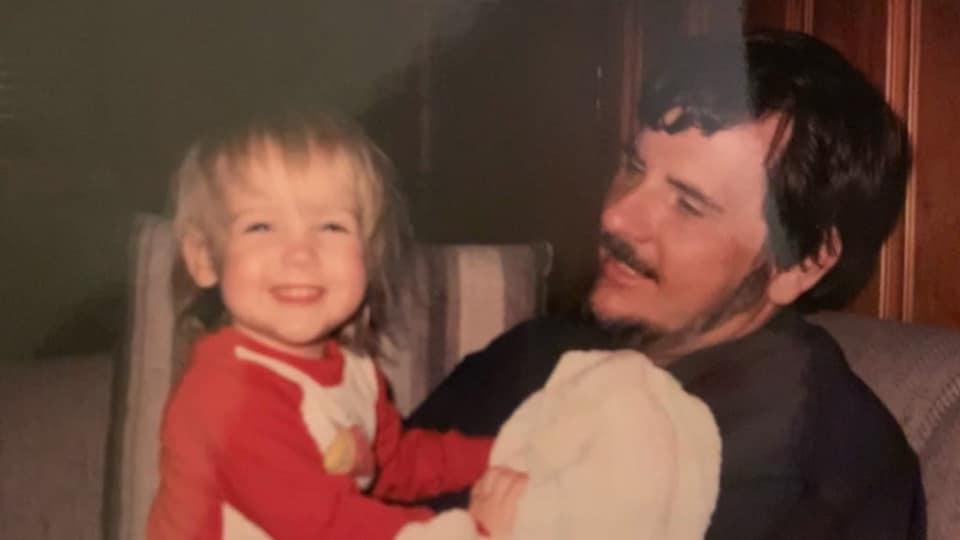

The following day, my brother called me to let me know of the passing of our brother-in-law, Carroll McNish, who was 80 years old. He was husband for many years to our older sister Gayle, and was a beloved member of our family. As his daughter put it, “he was my number one fan, and everyone he ever met’s number one fan.” He passed at home in Yukon, Oklahoma, (I know this from Gayle) surrounded by immediate family and two irrepressible border collies and his amazing collection of model cars and memorabilia. His service was just held in Oklahoma City, and the affection of all for Carroll was abundantly evident.

Leon Litwack was a renowned American historian, known all over the world for his books and lecturing; Carroll McNish was by trade a professional and master car mechanic and instructor at a Vo-Tech school, a community college in Oklahoma City, and a General Motors Training School for many years, alongside many other jobs that he held. He was also a person who seemed to be able to fix anything, a rare quality among the men of our family, who generally are hopeless at such things. Well, me, at least.

Leon grew up in Santa Barbara, California, the son of Jewish immigrants, sailed the world as a young man working on ocean liners, and had a lifelong intellectual fascination with the American South and with American folk culture (I often heard him and a few of his colleagues fill out the roster of their fantasy Jewish all-time all-star baseball team, with Sandy Koufax starting on the mound); Carroll grew up in Del City, Oklahoma, and was a fan of automobiles, stock car racing, recreational vehicles, puttering about in the garage, driving my sister to agility trial competitions for her border collies, the Oklahoma State Cowboys, the Oklahoma City Thunder, country music, and, most recently and delightfully strangely, cross-fit competitions.

Carroll’s stories and speech came from the stuff of everyday life. He had a tone of voice in speaking (albeit pitched at a baritone rather than a tenor level) that reminded me of the singer and fellow Oklahoman Vince Gill. Carroll was exactly the kind of person that Leon loved to talk with, in part to understand an American history that he felt had been denied him in his younger years, when “history” consisted of learning about Great Men and their Great Deeds. His career was about rewriting American history with people (good, evil, indifferent, brilliant, humanitarian, sociopathic — whatever their condition was) at the center. And, I suspect, they shared a mutual disdain for various kinds of political hypocrisies.

I know for sure they shared a mutual disgust for laziness and incompetence in their chosen fields of endeavor; ” deadwood” was Leon’s damning epithet for non-productive faculty members who neither published much or taught with the fierce passion that he did, and Carroll had any number of words, printable and otherwise, for people who didn’t know what they were doing but charged you for doing it anyway — the deadwood in his chosen fields of endeavor.

Both were men who radiated humanity, kindness, a well-earned pride in their competence in their work, a sly wit tinged with just a touch of ironic observation of human foibles, and a profound caring for other people, expressed most of the time more through actions than through words. And both were also devoted to their respective crafts; towards the end of his teaching career Leon suffered a stroke while lecturing and insisted on finishing his course that day, much to the horror of his teaching assistants, while Carroll, much to my own father’s warm approbation, was working on something or other, a car repair if I remember correctly, the morning of his marriage to my sister. “That’s a man after my own heart,” my father, a fellow devotee of work and family and caring for others, said of him around that time. Later in his life, Carroll took up a job as a testing proctor for some testing company (the kind that administers the ACTs and SATs and those sorts of standardized exams); Leon, meanwhile, continued teaching after his stroke, still mentally sharp as ever but now with a gravelly voice, his vocal cords never fully able to recover from the damage they had suffered in the stroke. But giving up his teaching post was hard, as he loved teaching and took justifiable pride in his reputation as a master of that craft. Likewise for Carroll, giving up a work routine was difficult, and so he continued working even when he didn’t have to, and despite the pain he suffered from a previous bout with pancreatic cancer and other assorted ills that ravaged him late in his life.

One essential thing that united the two was a love for teaching what they knew well, and a love for students. “Carroll loved teaching, the automotive industry, and especially loved his students,” the program for his funeral says; for Leon, simply substitute the history profession for the automotive industry, and you have the same thing.

I like to imagine what sort of conversation Leon and Carroll would have had, if they had ever met. Perhaps it would have started awkwardly, as both had some innate shyness and liked to repeat stories as a way of making conversation. But once Carroll would have started talking, Leon would have taken an immediate shine to him. Leon had an ear for authentic voices, and he loved listening to the stories of people talking about their lives. It was his great contribution to American history to bring those kind of people to the front and center of history, not because he romanticized them, but because he saw them as what history, ultimately, was all about. It was his calling, he thought, to bring them to the center of history, where they belonged.

Carroll’s soft Oklahoma accent and intonations would have appealed to him, and I can see Leon, clicking into oral historian mode, begin to ask him questions about what Carroll’s life had been like while younger, how he might have experienced the 1960s (everyone knows about Berkeley, but what was happening in Oklahoma City?); and what he had done as a Vo-Tech instructor, and what his favorite makes and years of cars were, and who his favorite country musicians were, and where might be the best barbecue or fried chicken place that he knew of in Oklahoma City.

And Carroll, once he got going on something, enjoyed talking and explaining how a certain piece of machinery worked, or why the cars lined up as they did as they rounded the curve on a race track, or why a certain kind of ethanol mix required in cars meant that the cars didn’t run as well, or why a particular home appliance broke down at the exact moment you needed it — or, most importantly, what his daughter Layne, my niece, had been up to lately (crossfit, it turns out).

Leon loved human speech of that sort, often quoted from it in his lectures, and struck up friendships with people from all walks of life in part because he loved to hear them tell their stories of everyday life that became part of his understanding of American history. His books are full of those stories, woven into masterful narrative interpretations of American social history.

In a way, the two had nothing in common; in another way, they had everything in common, each unerringly kind and supportive of those around them in their own ways, and both a master at communicating what they cared about, what they worked on diligently for many years, and what they wanted us to know about what was really important in life.

What a beautiful eulogy! Thank you for sharing their combined influence on your life. My sincere condolences to you.

thanks Angie! great to hear from you.

Thank you, Paul. This is a wonderful eulogy to both men, and it means a lot to me that you thought so much of them.

Thank you for introducing me to Leon Litwack, and for letting me get to know Carroll better. This is a beautiful eulogy, Paul.

Although I doubt that you will remember me from Beaver, (I was in Gayle’s class) that was the most beautiful eulogy I have ever read and feel that I know both men well now